After attacking Devil’s Reef in 1928, the U.S. government rounded up the people of Innsmouth and took them to the desert, far from their ocean, their Deep One ancestors, and their sleeping god Cthulhu. Only Aphra and Caleb Marsh survived the camps, and they emerged without a past or a future.

The government that stole Aphra’s life now needs her help. FBI agent Ron Spector believes that Communist spies have stolen dangerous magical secrets from Miskatonic University, secrets that could turn the Cold War hot in an instant, and hasten the end of the human race.

Aphra must return to the ruins of her home, gather scraps of her stolen history, and assemble a new family to face the darkness of human nature.

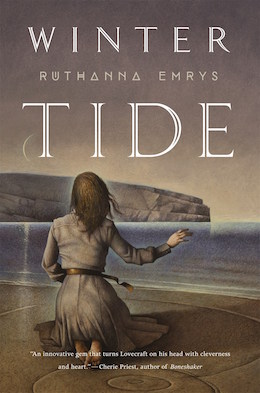

Ruthanna Emrys’ debut novel Winter Tide is available April 4th from Tor.com Publishing. Head back to the beginning of this new Mythos tale, or read on for chapter 3 below!

Chapter 3

December 1948–January 1949

Christmas followed close on Winter Tide. The Christian holiday first filled Charlie’s store with customers, then drew them all back into the seas of their families. Even he closed shop for the day and went to church services—awkwardly, I gathered, given his current beliefs. The Kotos, being Shinto, celebrated neither holiday, though Mama Rei and Neko surprised me after my post-Tide rest with a fish stew, studded with dried cranberries and salted almost to the traditional level for Innsmouth feast days.

To my relief, Charlie’s treatment of me didn’t change. The days between Christmas and New Year’s were quiet, and we spent most of our time studying in the back room. When we returned to the public area, we found that the gift-seeking customers had left it much in need of straightening. The pervasiveness of the foreign holiday had left me jittery: I fell to with a will, and spent happy hours sorting genre from genre and author from author.

Even the most ill-formed words, set to paper, are a great blessing. Still, I was not indiscriminate, and when I found a truly execrable passage in Flash Gordon and the Monsters of Mongo, I decided I’d enjoy hearing Charlie’s opinion. I drifted forward with one long finger marking my place, stopping occasionally to retrieve a book from the floor or straighten a row of spines. As I neared the counter, I heard Charlie’s raised voice:

“I don’t need you in here bothering my employee. Take whatever folders and files you’ve brought this time and get out.”

I toyed with the idea of letting Charlie drive him away. But as always, I could not feel safe turning my back.

I stepped out from my haven among the shelves. “It’s all right, Mr. Day. I’ll speak with him. Hello, Mr. Spector.”

He ducked his head. “Miss Marsh.” His eye caught on the book, and his lips quirked. I clutched it tighter, then forced my hands to relax. I let my finger slip from the page I’d meant to share.

A year and a half earlier, Ron Spector had walked into Charlie’s bookstore and asked for my help. The FBI had heard rumors of a local Aeonist congregation, doubted the group’s intentions—and wished to consult someone who wouldn’t condemn them merely for the names of their gods. For all his talk of better relations between the state and my people, and for all my acknowledgment that some people might use any faith to justify evil deeds, I refused to work for him. But I could not turn my back on the dangers of the state’s renewed interest in me—or resist the lure of meeting others who shared my religion.

It ended badly.

Afterwards Spector had sent sporadic notes from Washington, checking on my well-being. Perhaps it was some misguided sense of responsibility. I wrote back briefly, in minimal detail, not daring to ignore his missives entirely. He had not suggested any further tasks. There were, I feared, no other Aeonists in San Francisco, suspicious or otherwise. The rarity of my faith was the precise reason why he had approached me in the first place.

Over the past few months, these letters had dwindled, and I’d thought that he—or his masters—had given up the idea that I might be useful. I hadn’t been sure whether to welcome their apathy, or see it as an indication that my fellows were well and truly vanished from the land.

“You have something you wish to ask me. Ask it.” I braced myself, praying quietly for anything other than another ‘cult.’ I didn’t think I could bear another room of my fellow worshippers chanting familiar words and phrases that would turn out to be another mask for suicidal delusion. Or worse, for something more malicious than that self-proclaimed high priest’s desperate and contagious yearning for immortality.

And yet, if Spector told me of such a group, I didn’t think I could stay away.

He shuffled, glanced at Charlie. Charlie glared back.

“He stays,” I said. Then added: “He knows.”

Spector looked away, his skin reddening. I was not sorry to see his shame. He shook it off quickly enough. He took out a cigarette, tapped it on the counter, but didn’t light it. “I suppose you’ve heard about what’s happening with the Russians.”

One could hardly miss the papers—and I shared with the Kotos a fervent desire to see coming, early, the storms that might rile people against us. “Yes, the blockade in Berlin. Your allies are fickle.”

He shrugged. “They don’t see the world as we do. They expect every. one to think alike, act alike—and they’ll fight for it, if we let things get that far.”

In spite of myself, I shivered. The idea of another war… The World War—the first one—had taken so many of Innsmouth’s young men into the Army, returned many of them to sit blank-eyed and frightened on their porches—and perhaps triggered the paranoia of those whose libel brought the final raid on our town. The next war had stolen the Kotos from their lives and forced them to rebuild a community almost from scratch.

He continued. “ We’re working to stop them as best we can. There’s the new defense department, and the new agency for collecting foreign intelligence. I’m not involved with that directly”—he patted his suit pocket, as if I might forget the badge secreted there—“but we all work together, when we have to.”

“Of course,” I sighed.

“And the Russians have what, exactly, to do with Miss Marsh?” demanded Charlie.

“Nothing at all,” said Spector. “Except that someone’s gotten it into their heads that the Russians might use magic against us. And they’ve consulted with the FBI’s experts on—er—our domestic arts, to learn what they ought to do about it.”

I set the book down on the counter. “Mr. Spector, you don’t need me to tell you that magic makes a poor weapon. It’s not a tool for power, but for knowledge. And a limited tool, at that, unless you appreciate knowledge for its own sake. If your Russians are such scholars, you have little to fear from them.”

“We have little to fear from the magical arts that were legal in Inns-mouth.”

Charlie’s glare faltered. He knew the stories about what spells were forbidden, and why.

Spector pulled out a lighter and lit the cigarette. I stepped back discreetly. Charlie normally took his pipe outside in deference to my lungs, but I could hardly expect the same from others. Spector took a drag, and seemed fortified. “In short, they’re afraid that the Russians will learn how to force themselves into other people’s bodies—and use it not for personal immortality, but to take the place of our best scientists, our most influential politicians. The potential damage is staggering.”

“It is,” I said faintly. I thought about the bombs that had been dropped on Japan, and the potential for sabotage or theft in the secret places where they were kept. And I thought, too, about subtler things—words that could turn neighbor against neighbor, or government against citizen. “But I’m afraid I don’t have anything that can help you. To the best of my knowledge, there are no Deep settlements in the Pacific. If the Russians learned these arts, they didn’t learn them from us.” And while I could imagine one of our criminals deciding that switching with a Russian would put them sufficiently far from home to avoid capture, we would certainly have noticed if a bitter old man started speaking in a foreign tongue. Not to mention that most human versions of the art required direct contact, and Russian tourists didn’t generally visit Innsmouth.

“The Yith?” asked Charlie quietly.

“They don’t share their methods,” I said. “That’s why humanity’s versions of the spell are less powerful. But they all stem from imitations of visiting Yith. Russians could have learned that way as easily as any. one else; magic is no harder for men of the air than for us, merely less well known. And no, Mr. Spector, I know of no defense against body theft, nor any reliable way to detect it.”

He shook his head. “That’s not what I’m asking for—though I wouldn’t turn down a defense if you surprised me with one. The analysts believe they didn’t re-create the art on their own—but they may have sent someone to study at Miskatonic, some years back.”

While I stared, he went on, “I know you don’t like working for us directly. But I also know you have your own reasons for wanting to study that school’s records. We’ve persuaded them to accept a research delegation from the federal government. I would hope—that is, we wish to sponsor you to come along as a research assistant and language specialist. You’re more fluent in Enochian, and I suspect many of the other relevant languages, than anyone we can provide.”

I put a hand on the counter to steady myself. “Answer one question for me. Are you responsible for my brother’s inability to access the Miskatonic libraries, these past months?”

“No, of course not.” He shook his head vehemently. “Though we were aware of it. You must know that the, ah, activities of everyone released by Public Proclamation number 24 have been—kept abreast of—” Seeing my look, he hurried on. “But we’ve left him alone.” His lip quirked. “It might be better not to ask how we persuaded Miskatonic to offer our chosen scholars access, names unseen.”

“It might be better to tell me.” I crossed my arms. “Mr. Spector, I do want to see that library, very badly. But I will have no blood on my hands.”

He stepped back and held up his palms, a warding gesture echoed in a trail of smoke. “No blood, I promise.” He paused. “Miss Marsh, I wish you would give us some benefit of the doubt, however small.”

“I am willing to speak with you. To listen. It will take a long time for your masters to earn more.”

“The lady asked you a question,” Charlie said.

Spector sighed. “If you must know, there’s a partic ular dean with a penchant for carrying on with the maids. Not always entirely to their taste. His most recent girl works for us, and is a bit less easily cowed than the previous ones. He does us favors, sometimes, in exchange for keeping it all from his wife. And from the papers; Miskatonic prides itself on being a respectable school, after all.”

It was certainly as distasteful as he’d implied. I could hardly blame the woman for what she’d done—not given some of the favors Anna had won for us, when she was new to the camp and the soldiers grateful to suddenly find pretty, untainted girls under their charge. “Did you order her into that?”

“The girls get a certain amount of discretion in these things. You have to understand, she was already…” He trailed off, seeing something in my face, or Charlie’s. “She likes it better than her previous job.”

Not blood, then, on my hands. I swallowed and thought of the books. Spector was still good at making offers that I couldn’t find a way to ignore. And this time, I couldn’t refuse his offer and inquire on my own: without the state’s support, we’d remain as we were, with my brother hopelessly rattling Miskatonic’s gates.

If he needed us, I could at least set terms. “I won’t go alone. I’ll need my brother. And Mr. Day as well.” When Mr. Spector looked doubtful, I added, “His Enochian is coming along nicely,” though I suspected that was not where his questions lay.

April 1947: Much as I’d prefer to speak with Spector in my own territory, I meet him at the FBI’s local office. This conversation shames me, and I’d rather Charlie didn’t hear it.

The office is just outside Japantown, and shows signs of having lost staff in recent years. Spector, on loan from the East Coast, pulls chairs over to one of the empty desks with an apologetic shrug. Behind him, I see dusty file cabinets labeled in tiny, faded print.

“I visited the congregation,” I begin.

“I wondered if you might. If you’re willing to tell us about it, we could—” He stops himself. “Never mind. You found something you thought was important. Please go on.”

I try to guess what he didn’t say—was he thinking of offering payment? Should I be angry that he thought of it, or grateful that he thought better?

“They’re no threat to anyone else,” I start. “I want to make that clear. If you don’t believe me there’s no point in going on.”

“I believe you.” He sounds sincere enough. I wish I didn’t have to second-guess every word.

“They believe that they’re beloved of the gods, and that if one of them walks deep into the Pacific, unafraid and unflinching, Shub-Nigaroth will grant them immortality. Two of them went through the ritual before I got there. The others are convinced that their old friends are ‘living in glory under the waves,’ but I can assure you these people are entirely mortal—and the gods are not so attentive to human demands as they insist. Mildred Bergman, their priestess, is next. And—soon.”

“I’ll set something up,” he assures me. “ We’ll keep them safe. And Miss Marsh—I’ll do my damnedest to make sure no one treats them like the enemy.”

Neko came to me after the washing up, while I was working on a letter to Caleb.

“I want to go with you,” she said.

“Neko-chan, what for?” It took a moment for me to realize the source of my startlement: I still thought of her as the thirteen-year-old new come to the camp, and all too much like myself at the same age. But in fact she was nineteen, through with her schooling, more than ready to seek a husband or help support the household. She had been slower about both than Mama Rei would have wished, but that did not make her less an adult.

She twisted her hands together and stared at the floor. “I could go along as a secretary. You’ll need someone to take notes, and keep track of what you find.”

“I think the FBI already has secretaries.” I thought of the woman who’d paid for our entry with her own flesh, and shivered. I owed that woman something, though I doubted she would accept it even if I could figure out what it was.

“Your G-man would bring me along if you asked.”

“G-man?”

She shrugged it away. “Like in the movies. Please, Kappa-sama.”

I chose my words carefully, trying to explain something that had barely needed saying in Innsmouth. “Miskatonic University is not a nice place. The professors—they are old men, proud of their power, frightened of anyone who might threaten it. They care nothing for responsibilities or obligations outside the school. They are not evil, but nor are they good to be around unless one has a truly important reason.”

Her eyes slid toward the kitchen, where Mama Rei still remained sweeping. “You go out in the rain, without an umbrella or a coat. And you come home wet and happy.”

I smiled in spite of myself. “The water is good for me.”

“But it’s not just that.” She glanced at me, suddenly shy in a way that reminded me more reasonably of her younger self. “It’s a thing you couldn’t do, and now you can. Mama doesn’t understand, but—please forgive me, but when you were my age, you were still there, but I’m here and I don’t want to waste my freedom just taking dictation from old men—and there are plenty in San Francisco, too!”

“Old men who love power are everywhere, I’m afraid,” I admitted.

“I know. But I think that travel could be the rain, for me. And Mama will never let me try it, not if we had to pay, even if we could afford it.

But if I’m going along with you, if you asked, she wouldn’t argue. And then I would know. If it’s what I should be doing.”

Few enough of us get to do what we should be doing—assuming that such a thing even exists. I would not be the one to forbid her the rain.

We live in a world full of wonders and terrors, and so I cannot entirely fathom why my first aeroplane flight struck me so. Or perhaps I can: it was the first time I had left San Francisco since following the Kotos there. I felt vulnerable amid the cloying smoke and the crowd of well-to-do strangers at the airport. The women especially, with their makeup and store-bought dresses, watched us with unsympathetic eyes.

I dared not forget how we looked: a herd of odd and lame animals passing cautiously among predatory apes. Neko pressed close to me, and Charlie and Spector walked ahead to either side. I was grateful for their protection. Spector had a better gait for it, and a sturdier gaze. Still, I caught snickering whispers from a few who had picked out some Jewish aspect of his features, and I was grateful when at last we settled into our seats, away from the eyes and opinions of the susurrating crowd.

And then to go from that to the great machine gathering speed, leaping into the air and slipping through the clouds and into unexpected sun. Normally I prefer rain and fog, but somehow I felt safe, knowing that those things still caressed the city below—and behind, as we traveled swiftly onward. It was a perspective akin to meditating on the space between the stars, or the rise and fall of species over aeons. I saw more truly than ever that even a single day, on a single world, can contain both atrocity and kindness, storm-tossed seas and burning deserts. On such a world, lives may never touch and yet still give solace by the reminder that one’s own troubles are not universal.

I yearned to share my thoughts with Charlie, but he sat farthest from me, across the aisle. I considered trying to explain it to Neko, but even that would attract Spector’s attention. So I stared out the window as we soared over snow-brushed cyclopean mountain ranges, lifeless desert, and endless stretches of cleanly pressed farmland shadowed by dusk, before I fell asleep dreaming of the unfathomable lives of strangers.

The landing in Chicago was rough. The little plane shuddered down through a wild wind, bumping at last onto the tarmac while I considered whether it was worth drawing a diagram on the seat-back in front of me to try and calm the gale. Once we landed, I could see the softly pattering rain around us, barely blowing at an angle, and realized that the apparent storm had been an illusion of our speed, or of the plane’s own fragility.

As we milled in the terminal, waiting for our connection, I found myself oddly at ease: the predators all looked as tired as we were, and paid us little attention. I slumped on a chair, glanced over, and found Spector settled next to me. The skin below his eyes darkened with fatigue, but the eyes themselves flicked constantly. I realized that he, too, noticed every person who came within a few feet.

Of course, he caught me watching him as well, and smiled ruefully. “My apologies, Miss Marsh. Whenever I’m up late, my instincts start telling me I’m on watch. It doesn’t seem to do any harm, and it keeps me awake.”

“Ah.” Of course, he’d fought in the war. Most men had.

“European theater,” he added, giving me a considering look.

I nodded, quietly relieved that he’d never been in a position to kill any of the Kotos’ relatives. Or more likely, given his specialties, provide intelligence to those who did.

He leaned back and rubbed his eyes. “Miss Marsh—when we get there…” He hesitated.

I waited for him to go on. “Yes?”

“Just bear in mind that this kind of mission can accomplish more than one thing.”

Fatigued, I could just resist giving him an extremely impolitic look. “Mr. Spector, I can be discreet. But my talent is not in working ciphers.”

His eyes returned to their watchful rounds, then focused on me once more. “It can wait, I think.”

He looked uncomfortable enough that I was tempted to let it go. But I found myself equally uncomfortable allowing him to decide what I’d think urgent. ”I’m not fond of answerless riddles, either. I don’t want to walk into Miskatonic with my eyes closed, if there’s any alternative.” I added, lowering my voice, “I have good ears. Speak as softly as you like, but please tell me what I need to know.”

He hesitated another moment, and I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to push him further. But at last he relaxed and tensed at once, in the way of someone who’s made an unpleasant decision. “You know I was out of touch for a few months, before I contacted you.”

I nodded. “I assumed you realized there wasn’t much more I could do for your masters. They didn’t want you speaking with me?”

“We usually refer to them as Bureau leadership, but no, they didn’t. It wasn’t anything to do with you, though. I don’t know how much attention you pay to the news, but when Israel declared independence last May, our higher-ups started worrying about the Jews in service. I got a whole interrogation about whether I was planning to leave the country, whether I considered myself an Israeli citizen. A couple people quit over that, and one did emigrate. Said he might as well fight for someone who appreciated him… anyway, they took me off anything active for a while. Not officially, but they obviously wanted to keep an eye on me.”

“Oh.” I vaguely remembered reading about the new country, but I hadn’t made the connection somehow. His own people, half slaughtered in the war, had gone without a home for a significant chunk of the recent millennia. “So now they’ve decided to trust you again?” I almost asked why, but realized that it would be both rude and unnecessary.

He shrugged, gave a rueful smile. “ They’re giving me a chance, let’s say. Because I’m the one with a reputation for talking to the people they need.”

I frowned. “So you… need us to find something. For your career.”

He shook his head. “They aren’t stupid enough to encourage false alarms like that—and frankly, I’d rather go back to New York and work in my father’s deli than betray them that way. I’ve seen enough of the files to think there’s a real chance that something’s going on, but even if this turns out to be a false lead I don’t think they’ll hold it against me. Whatever we find, the work needs to look good—and it needs to be good. I need to show that what I do still matters, even when the threats they care about change.”

I considered, pushing through fatigue to see what he was driving at. “What you do—is talk to me. To us. To Aeonists and people of the water. You need to prove that we’re still useful.” And therefore, from the state’s perspective, that we still had a right to exist. I wrapped my arms against a chill that had little to do with the winter draft creeping through the plate windows.

He nodded. “I’m sorry, but yes. There are people higher up in the Bureau who’ve argued that Aeonists, as threat or resource, are no longer relevant. Like Nazis”—he didn’t quite keep the bitter irony from his voice—“a sociopolitical relic of the first half of the century, when we need to worry about the threats of the fifties.”

“Until 1928,” I said, “we thought we could survive by being ignored. We were wrong.”

“I don’t intend for you to be ignored,” he said firmly. “And I don’t believe that whole peoples and religions become irrelevant. It still matters that we can work together, and I plan to prove it.” He ducked his head, suddenly diffident. “And yes, I know it isn’t right for that to be necessary. For what it’s worth, I’m sorry.”

On the next flight, I slept particularly badly.

Excerpted from Winter Tide © Ruthanna Emrys, 2017

I’m enjoying this quite a bit. Looking forward to the next couple of chapters.

Heh. “Cyclopean mountain ranges.” I saw what you did there!

S

I am liking what has been done so far. I will be most interested to see this incarnation of the Miskatonic University.